Bottled Songs: My Crush Was a Superstar

(a chapter from Bottled Songs, a series of four short films co-authored with Kevin B. Lee).

A mesmerizing account of an investigation that is both intellectual and artistic, both political and personal.

Filmscalpel (video essayist)

Synopsis:

This short film tracks a French ISIS fighter through a trail of messages, videos and postings to uncover his existence in both social media and reality. This leads to an uncomfortable first-person exploration of the gender dynamics behind ISIS recruitment strategies.

This film is not currently available for screenings.

One of Sight & Sound's Best video essays of 2017.

One of Jonathan Rosenbaum’s Ten best films of the year.

Public screenings and installations of the work include:

Parallax Forum in Katowice 2019 (Poland)

“Networked Effects” Exhibition at the Oodi Library in Helsinki 2019

NEoN Digital Arts Festival 2019

Uppsala International Short Film Festival 2019

Visite Film Festival 2019

Tatsuno Art Project 2019

WRO Media Art Biennale 2019

Ars Electronica Festival 2018

Impakt Festival 2018

Rencontres de Bandits-Mages 2018

Essay Film Festival London 2017

As part of Bottled Songs 1-4, the film also screened at

Open City Documentary Film Festival 2020

Kaunas International Film Festival 2020

Camden International Film Festival 2020

2020 Logan Symposium - Centre for Investigative Journalism

Stuttgart Filmwoche 2021

Document Film Festival 2021

IFFRotterdam 2021

This video HAS ORIGINALLY BEEN PUBLISHED on NECSUS - European Journal of Media Studies, accompanied by the following statement:

The video is the first version of a chapter from the Bottled Songs series, an audiovisual investigation of terrorist propaganda in the age of social media, in collaboration with Kevin B. Lee. The project aims to explore the contents and contexts for production of terrorist media and to question how these images migrate from social media to news broadcasts, from phones to computers, from the Middle East to other regions of the globe. This specific video explores the online presence of a French-Moroccan jihadist who died in Syria in 2014.

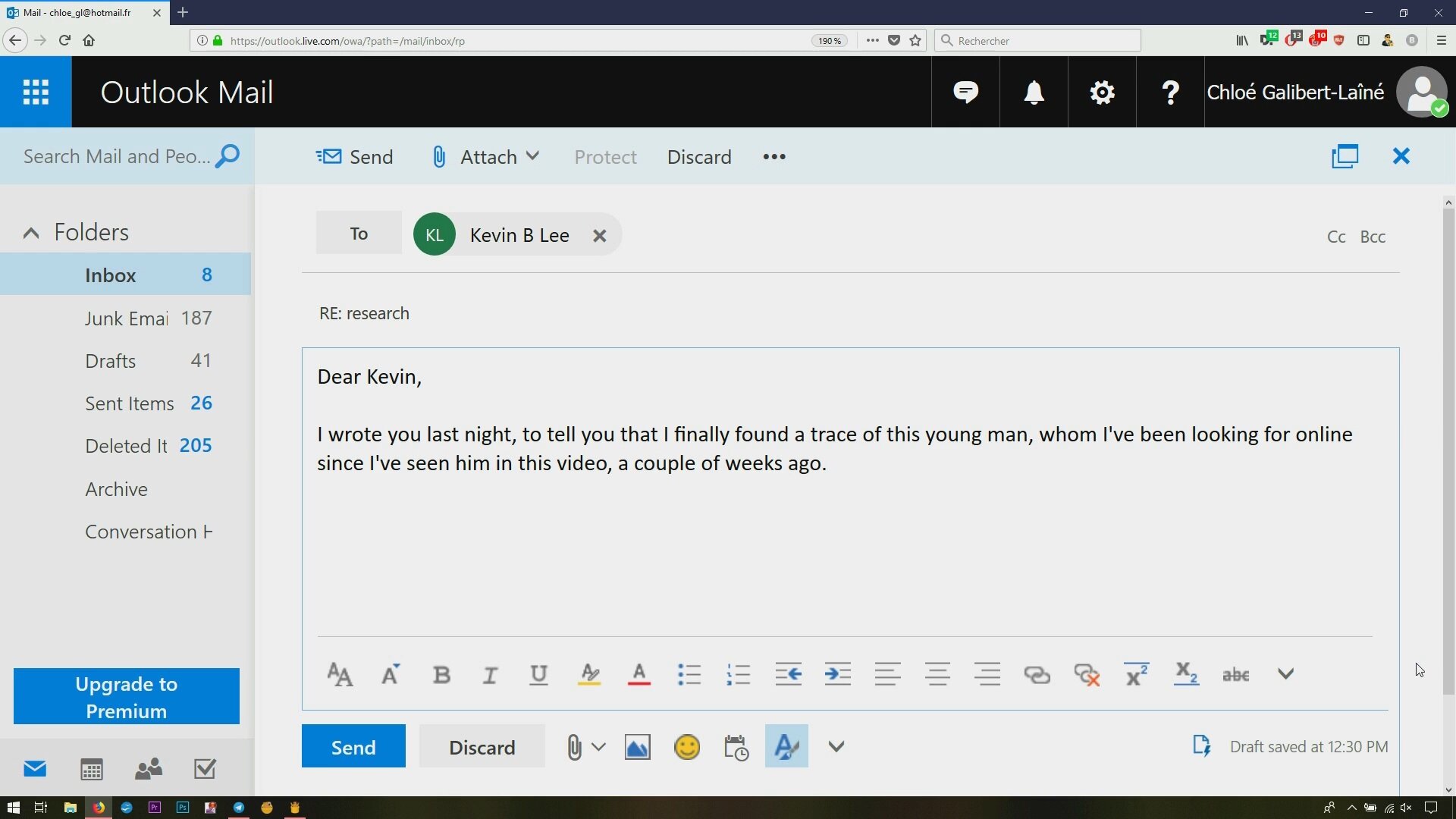

This investigation started with a ten-second amateur video I found somewhere in the middle of a television program dedicated to online Islamic propaganda – on a makeshift bed a young man conceals his drowsy face under a light blanket as another man cheerfully tells him to get up. For some reason this clip aroused my curiosity. I think I had the feeling that if I were to produce a documentary on ISIS recruits I would pick him as a character. I tried to identify him and gather visual material in which he would appear. I soon realised that among the hundreds of young French men who joined ISIS in the last years he was one of the most visible online. He was very active on social media where he would regularly post pictures and videos of his everyday life in Syria. As amateur contents constitute an important source of information for international journalists his posts would also appear in many Western publications. At some point it seems that he had become one of the official faces (and voices) of ISIS online propaganda.

However, this video is not a portrait of this man. If anything it is an exploration of the reasons why I felt prompted to track him and not another jihadist. What is it that made him such a remarkable, popular emissary for ISIS? Why did I immediately spot him as a potential character for my project? I thought that questioning my own drive toward him could be a productive (yet extremely uncomfortable) way to explore the selection process that allows some individual figures to emerge from the mass of audiovisual data that is uploaded online every day. This also led me to question my expectations and bias at this early point of my research – as someone whose limited knowledge about Islamic terrorism comes exclusively from reading mainstream Western media and academic studies, I started exploring this material with preconceived ideas about what and whom I expected to come across. To that extent my eagerness to grasp this man – a Maghrebi, Muslim, attention-hungry, media-savvy millennial – as a representative of ISIS recruits can only speak to the rush with which one hangs on whatever confirms one’s prejudices instead of paying attention to things that might take place off one’s radar.

I soon realised that another unexpected dimension was also feeding this inquiry: simply by virtue of my gender this investigation became not only that of a researcher who looks at a subject of inquiry but that of a woman who looks at a man. It was only natural that the narrator leading the investigation should be female. As in my previous video work I simply recorded my own voice. In this case though I felt that the choice to include a female voiceover had a strong resonance with the subject matter of the video. It is indeed a very common narrative that asserts that romantic attachment accounts for the departure of young European women for Syria. After having met an attractive young jihadist online the woman would get married on Skype and a couple of weeks later leave her country to join him in Syria where the digital marriage would be officiated and consummated. When exploring why this man’s face had caught my eye in the first place I had to be aware that some of the motivations I would uncover may account for why young women, in some ways similar to me (French women in their twenties), would take such a major decision as to leave their families and join a terrorist organisation. In the world of terrorist media there are very few representations of female bodies or voices (as the doctrine of Islamic iconoclasm sentences women to invisibility). As a reaction to this visual taboo within this world of stereotyped, ideologically-biased images, my video tries to open a space for female gazes.